Pursuing colour to the end

In a dim gallery of a museum of modern art, a year is on display.

There are the wind chimes and bellflowers of summer, ears of autumn rice and the first snows of winter, the culmination of an exhibition that begins with the flowers of spring.

But it’s not bells, grain and ice that have been arranged behind museum glass. Filling the cases like so many paintings are kimonos woven by an 88-year-old artist honoured by the Japanese government as a Living National Treasure. The pieces at the Museum of Modern Art in Shiga, the prefecture just east of Kyoto, are not still life works. The kimono titled Wind Bells has clusters of little purple lines scored into a white base: not pictures of wind chimes but their pinging transcribed.

Artist Fukumi Shimura does not depict life; she suggests it.

It has taken centuries for kimonos created through tsumugi weaving – Shimura’s speciality – to be recognised as art. Broadly speaking, kimonos can be divided into two kinds: those woven from threads that have already been dyed and those where patterns are dyed into white fabric. Most of the kimonos worn today belong to the latter kind.

With their simple checks and stripes and woven from empty or deformed silkworm cocoons, tsumugi has long been seen as the poor country cousin of the kimono world.

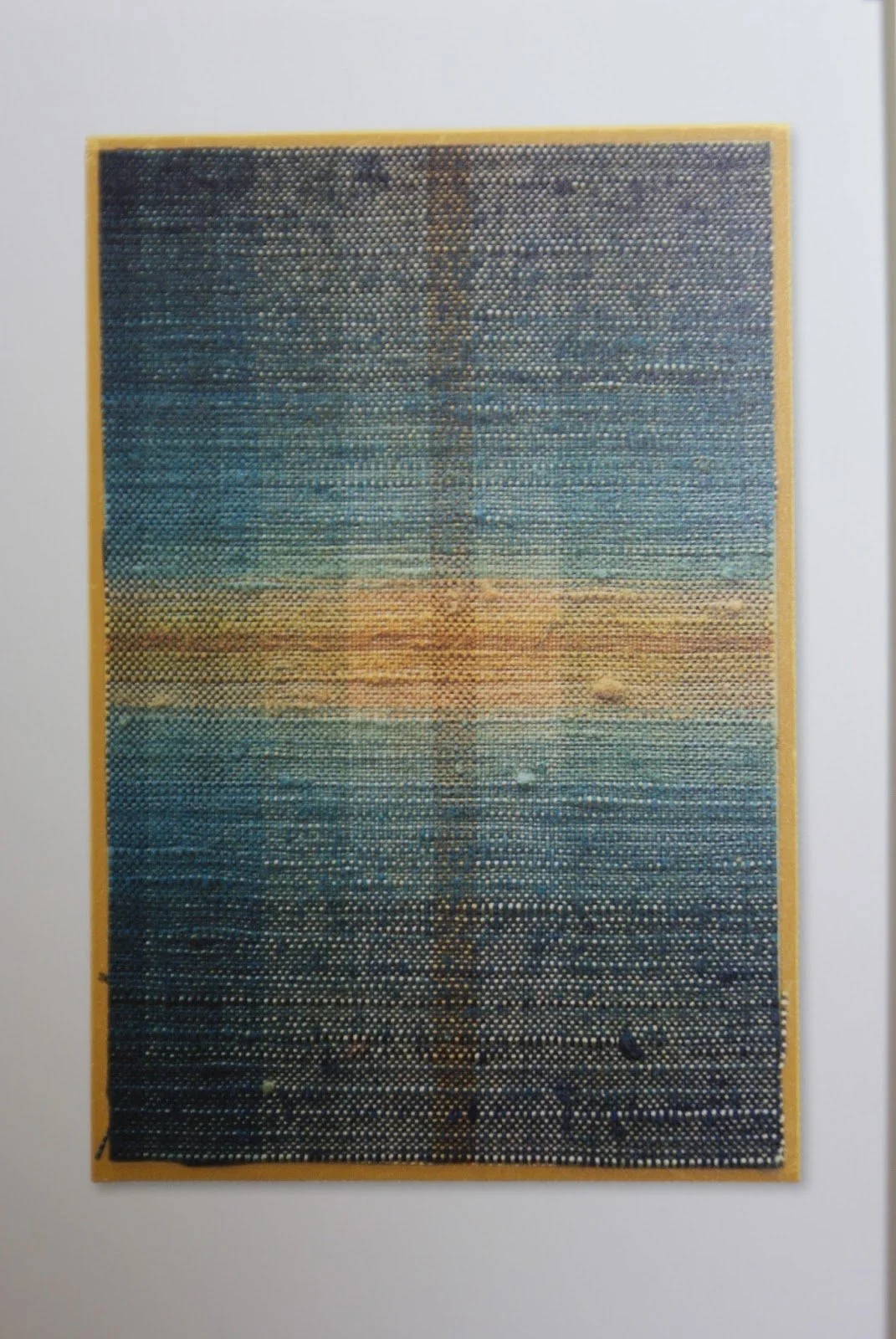

But building fabric thread by thread can create a depth and gradation of colour impossible in dyed cloth.

Tsumugi weaving depends heavily on the threads; Shimura uses those dyed at her own workshop in Kyoto. Her colours come not from mixing chemicals but from boiling plants such as gardenia – the fruit gives a bright yellow and – onion skin, which yields oranges and browns.

‘In every plant is a pure colour,’ Shimura said on The Professionals, an NHK documentary series which featured her in May.

But behind the serenity of many of her works is a life with more than the usual share of turbulence.

Born in Shiga, Shimura was sent away as a baby to relatives in Tokyo who raised her. At the age of 16, she visited her real parents’ home, discovering there an old loom. It belonged to her mother Toyo, who had been inspired by a folk craft movement but shelved her ambitions to support her husband’s work.

She became Shimura’s first weaving teacher. Another family member proved to be a great influence: a brother five years older whom she became deeply attached to. Motoe wanted to become a painter but collapsed from tuberculosis after the war.

Shimura still remembers what he painted as he was dying, works flooded with a brilliant, burning red. ‘I wasn’t thinking of weaving as a career then,’ she said in the NHK feature. ‘But those colours sank into me.’

It was as if he was trying to do as much as he could in whatever time was left, she said. And the time he had left was little: Motoe died not long after his collapse at the age of 27.

For a while, Shimura managed to lead a normal life, becoming a housewife in Tokyo. But upheaval returned when she found out about her husband’s infidelity and divorced him. She now had to work – she had two young daughters to support – but what could she do?

She remembered the loom in her mother’s house: she would weave kimonos for a living.

Her decision met a chorus of disapproval from her relatives. She had no training, no experience, they said, calling her an irresponsible parent.

She did it anyway, leaving her daughters in Tokyo and returning to the west of the country, to her mother in Shiga, where she began her training in earnest at the age of 31.

Shimura readily acknowledges the enormity of her decision to go without her children, calling it a great crime, a deep sin.

The first few years were difficult: the pieces she wove did not sell. She remembers the guilt she felt then, a mother who had not only left her children but could not even afford to send them sweets.

She pushed on anyway and gradually recognition – and buyers – began to trickle in.

With a career of almost 60 years behind her, Shimura still shows every sign of being a woman fascinated by her work.

‘The best colours,’ she said, ‘are those that cannot be said to be colours at all.’ For her, indigo is not just a dark blue but something that impresses upon you the depth of life.

Dyes have been extracted from plants for more than a thousand years in Japan, with indigo regarded as one of the hardest to handle. The dye comes not from boiling the plant but by fermenting it in a large vat. The temperature has to be taken every day and adjustments made. About a week later, if fermentation is progressing, a flower-like froth will appear.

Shimura began working with indigo 45 years ago but it was only when her daughter Yoko, now also a superb textile artist, began to help that she managed to achieve a stable colour.

She compares the process to bringing up a child. If the indigo is raised properly, it will reward its parent with a deep blue.

Like humans, the vat of indigo has a lifespan. After about two months, the froth will disappear and the indigo will die. But just before it does, it will yield a particular shade known as kame nozoki – a glimpse of the vat.

Shimura describes it as a light, clear blue, the afternoon sky after a shower. But even after almost half a century, she does not think that she has achieved it.

‘Colours I’ve never seen before – that’s what I search for,’ she said.

So now even as she approaches 90 and regardless of the honours she has already won, Fukumi Shimura is still searching for what eludes her, for the colour granted only at the end of life.

An indigo-based kimono titled Autumn Moon (秋月) at Gallery Fukumi Shimura in Kyoto.